Cheating, plagiarism and academic misconduct are not new challenges for colleges and universities.

The earliest recorded cases involved cheating on a civil service entrance examination in China thousands of years ago. Cheating on exams and bribery for academic honours was written about in The Book of Swindles published in 1617. Benjamin Franklin also had to retract a 1756 paper for reasons of inappropriate use of other people’s data.

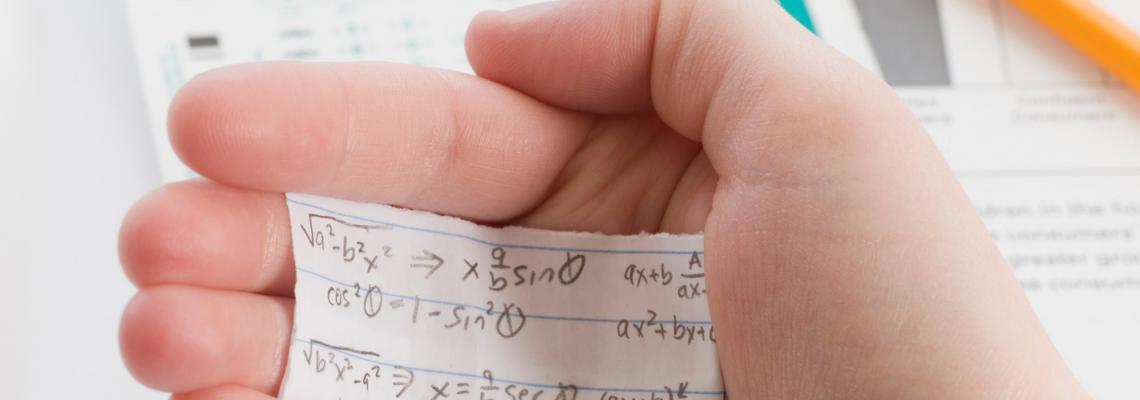

But we have to acknowledge that academic misconduct is now a significant problem. One recent publication suggested misconduct and plagiarism is the new “arms race” in higher education. Essay mills, custom writing services, paid exam takers, partners undertaking assignments for their loved ones, and some parents completing assignments for their offspring are all part of the problem and there are no easy solutions.

The scale of the problem is substantial. A 2018 study from Turnitin suggested 16% of the 38.3 million papers analyzed by their software matches papers developed by essay mills. In an analysis of cheating, between 3.5% and 7.9% of students surveyed across the world admitted to paying for writing services. One study suggests the figure could be as high as 22%,with some students buying more than one paper. Canada ranks 4th in the world for these kinds of purchases.

Many students, especially international students, seem unfamiliar with the misconduct regulations and requirements. A 2016 study of more than 100 United Kingdom (UK) universities by The Times found non-European Union (EU) students were four times more likely to be caught cheating than UK and EU students. In the United States (US), international students were found to be five times as likely to be caught cheating than their local peers, according to a Wall Street Journalanalysis of data from 14 leading US colleges.

Academics themselves are not immune. The rate of retraction of academic papers has risen significantly. Between 2003 and 2009, the rate of retractions doubled as the number of papers published also doubled in this same period. Four out of every 10,000 papers published are subsequently retracted, mainly due to fabrication or fraud. Approximately 2 million academic papers are published each year. How can we expect appropriate behaviour from students when they can read about faculty who do not model appropriate behaviour?

<h2What Can Be Done?</h2

1. Outlawing Essay Mills

Essay mills and writing services, though illegal in some parts of the world (including 17 US States and New Zealand), are legally offering these services in Canada, the UK and many other parts of the world. Making them illegal may not stop the use of these services, but it would help.

Some have argued this would force these services underground and would not stop students finding these services, making it more difficult for the essay writing services to operate would help curtail their use and possibly make their services less affordable.

Consideration should also be given to the withdrawal of student visas for those found to have engaged in academic misconduct and fines could also be levied. The penalty for using essay mills ought to be substantial to deter students from even considering using them.

2. Educating Faculty

It is not enough for a college or university to have a license for plagiarism detection software. Faculty should see a part of their role as detection and reporting. To do this, they themselves need to be aware.

Some colleges and universities require their instructors to complete a short cybersecurity and privacy course before they can begin teaching each academic year. One university provides courses to their faculty that consist of two short modules, which together take 30 to 40 minutes to complete. Faculty must successfully complete two multiple-choice quizzes with a pass of 75% or higher before their access to the university systems such as e-mail and library services are renewed. No such requirement exists for instructors related to cheating and academic misconduct. It may be time to introduce this.

In particular, many faculty are unfamiliar with the power of the analytics that all learning management systems (LMS) produce. Such data are helpful in revealing what students are doing on the LMS, how they are using the resources provided, and whether or not the patterns of their behaviour are consistent. It can also reveal the level of interaction between students, and between students and each component of the course materials.

To strengthen the importance of this role, clauses could be negotiated as part of collective agreements that require them to both commit to learning about academic misconduct and reporting students when “caught” cheating. A simple development might be to ask faculty to develop their own versions of an academic integrity checklist.

3. Educating Students

Students need to know three things:

-

-

-

- What the academic integrity assumptions are;

-

- What the consequences of breaking the rules look like and how the process of academic discipline works; and

-

- What they can do to ensure they comply with the rules.

-

-

Case examples of what happened to students who are “caught”, such as suspensions, expulsions, loss of credit, withdrawal of degrees, diplomas and certificates, are all powerful ways of sending messages. Sharing policies and regulations are not effective in and of themselves. What students need is a connection to them and to understand that breaking the rules has consequences.

What helps in this work is for faculty to know their students – what they look like, their backgrounds, their ambitions – and for students to know that faculty know them as a person. Building engagement is not only good for academic outcomes, but also builds trust.

Like faculty, students need basic education. A short course, which students are required to complete, and shows them:

-

- How to reference and acknowledge the work of others (which is helpful to all faculty who teach and have to keep making the same points over again);

-

- How to use the plagiarism features of an ad in Word or Google Docs; and

-

- How the college or university uses cheating detection software, which strengthens their understanding of acceptable academic behaviour.

Where peer assessment is used, student assessors need to understand that part of their role is to “call out” clear examples of poor referencing, cheating or plagiarism. This also reinforces the culture of integrity.

4. Focus on Student Engagement

The best predictor of learning outcomes, student retention and completion is the extent of student engagement: the more engaged, involved and active the student is, the less likely they are to cheat and engage in academic misconduct. This requires the design of learning to focus on the student creating resources, such as mind maps, storyboards, case studies, blogs, short reviews of papers or chapters, commentaries, videos, presentations, rather than just completing quizzes and exams.

While this learning needs to be “scaffolded”, shaped using templates or prototypes, it is more likely to enable students to produce their own work than reproduce the work of others. It also quickly becomes clear what the unique “fingerprint” or style of the student is. A class of thirty produces a variety of different approaches to the same topic.

More importantly, by creating a high level of engagement and a sense of community of inquiry, the incentives for misconduct are lowered. Students have a better understanding from the instructor and their peers of the performance expectations and “rules” than when the learning is formalized lectures and exams.

5. Rethinking Assessment

A key part of the problem is colleges and universities still focus on “assessment by trial”, as one student calls the mid-term/end of term examination process, namely proctored examinations.

Proctoring technology systems, whether for in-person examinations or remote examinations, are becoming more robust and reliable. Using facial recognition, fingerprints and other technologies can affirm the student taking the examination is the same student who is paying for the course and attended lectures and or synchronous sessions. These are helpful developments. But, this is an expensive solution and one that complicates rather than simplifies, especially now that students are challenging the legality of facial recognition systems.

Continuous assessment, based on a variety of different tasks and challenges set during a course of study, all linked to the knowledge, capabilities and skills being developed in a course, provides a more sustainable solution. This assessment can also involve an evaluation of “soft skills” – critical thinking, problem solving, teamwork, communications, leadership, adaptability and emotional intelligence. Though more demanding of the instructor, continuous assessment provides an opportunity to triangulate student performance, especially if authentic assessment is a key feature of these assessment designs. Different kinds of assessment over the course of a semester create a deeper understanding of the students’ knowledge, skills and capabilities.

Such an approach can also take into account issues of inclusion, accessibility, access to technology and cultural backgrounds. Authentic assessment, where a student can choose how they want to present their work and what they want to include in their portfolio, can also be helpful.

Part of the reason for academic misconduct is the competition over grades. At some universities, it is unacceptable to use the full grading schema for a class of students, all “have to have” grades between A+ and B+. Awarding a C or D is seen by students as an abject failure. This is why some institutions moved to a simple pass/fail. This takes the student focus away from the subtlety of grades and lets them focus on the work they are expected to produce.

6. Deploying Technology

Plagiarism and cheating detection software has been with us for some time. Turnitin.com, amongst the best-known products, was founded in 1997 in California. It spawned a whole industry. There are now over fifty products on the market at this time, including Grammarly, ProWriting Aid, Whitesmoke, Duplichecker, Quetext, Dustball, and Unicheck.

There are also new tools available. Educational data forensics looks at patterns of student behaviour on LMS and their computers, when they study, how long they study for, the patterns of browsing, how they prepare for and write assignments, and how they type on the keyboard and then compares how a submitted assignment was done versus their normal pattern. It was uncovered that a cheater uses different patterns than the registered student. The software currently used for such detective work includes ecree.com and Elute Intelligence, which make extensive use of analytics generated automatically by every piece of software the student uses.

A third category of detection software was deployed at scale in India by the National Testing Agency (NTA). The algorithms used are preprogrammed to detect twenty different patterns of cheating on multiple-choice examinations taken in person on Internet-disabled computers. If a cheating pattern is detected, the live invigilators are alerted and asked to intervene.

Some institutions are now deploying blockchain technology for traceability and verification. Some conceptual models are available and several colleges and universities around the world deployed blockchain as a way of managing the students’ learning e-portfolio and certification. One feature is a credit earned and placed on the blockchain by a college or university can be instantly removed if cheating is confirmed.

Other assessment related technologies are also now being deployed, including automated marking and feedback software. Free to use software like TAO, powered by artificial intelligence (AI), can be used to create, mark and provide feedback to essays, short problem statements, quizzes and other forms of assessment. Bolton College in the UK is using natural language processing (a form of AI) to provide instant feedback to students through a virtual assistant. Several other institutions are doing the same.

A particular challenge relates to group work and team projects, whether in science labs or fieldwork or in a project activity. Peers are often reluctant to call out fellow students who do not “pull their weight” but instead rely on others to get the work done. The use of structured peer assessment programs, like Kritik or Teammates enables students to evaluate the contribution made by their peers as well as provides a basis for students to give feedback to their classmates. Rubrics in which the specific contribution of each person have to be assessed by all team members are also a way of dealing with these issues.

Sometimes, however, the whole team cheats to get a result – they collaboratively fabricate data, descriptions of field visits not taken or suggest outcomes that did not in fact occur. This is more difficult to detect – it took years to detect data fabrication by the psychologist Sir Cyril Burt and his team. Vigilance and expert faculty knowledge are key. Using oral presentations and in person reviews of the evidence base for projects will often uncover such collaborative cheating quickly.

7. Developing A Culture of Integrity

In sports, trying to develop a drug-free culture is a continuous and demanding challenge. New energy supplements and new performance enhancing drugs are discovered and used by athletes all the time. The consequences of discovery can be severe, including lifetime bans, country exclusions and the revoking of medals, records and awards. Despite elaborate campaigns and significant expenditure on testing regimes, cheating continues, especially at the highest levels of any sport. It is the same in the academic world. It is an ongoing challenge.

What matters to celebrate excellence and to use all of the tools available to showcase what excellence in teaching, learning, assessment and quality research looks like. While the technology can help, the key is to build a sense of community and a level of engagement that makes cheating and misconduct a social “no-no”.

Alongside of this, there must be severe penalties and a very public sharing of examples of cheating, fraud, fabrication and plagiarism so a community of teachers and students know these behaviours have consequences. Cheating and academic misconduct damages all, not just the individuals who are “caught”, including the reputation of the college or university.

By showcasing excellence and revealing lapses of judgement or inappropriate academic behaviour, over time, the culture of integrity should improve. That’s the theory but it is a long journey. Building a culture of integrity will always be a work in progress.