Opportunity

Professor Joan Sharp, in the Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University(SFU) in Burnaby, British Columbia, teaches courses in which one of the aims is to develop a better understanding of some of the controversies in biological sciences.

However, she constantly found herself running up against students’ inability to put forward an evidence-based argument, even in third year classes. Students were expecting the evidence ‘to speak for itself’. Many students firmly believed that in science, there is always one ‘right’ answer to every issue, and the students’ expectation is often that instructors will provide them with that ‘right’ answer.

When Professor Sharp studied this issue more fully in the science education literature, she found that this is a common and widespread issue and not specific to her classes. She also discovered that in SFU’s Department of Education, graduate student Dr. Hui Nui, collaborating with Professor John Nesbit, had designed a Web-based argument visualization tool called the ‘dialectical map’ or ‘DM’.

Professor Sharp, working in conjunction with Dr. Hui and Professor Nesbit, decided to adapt the map for those of her classes that covered controversies in the biological sciences.

Innovation

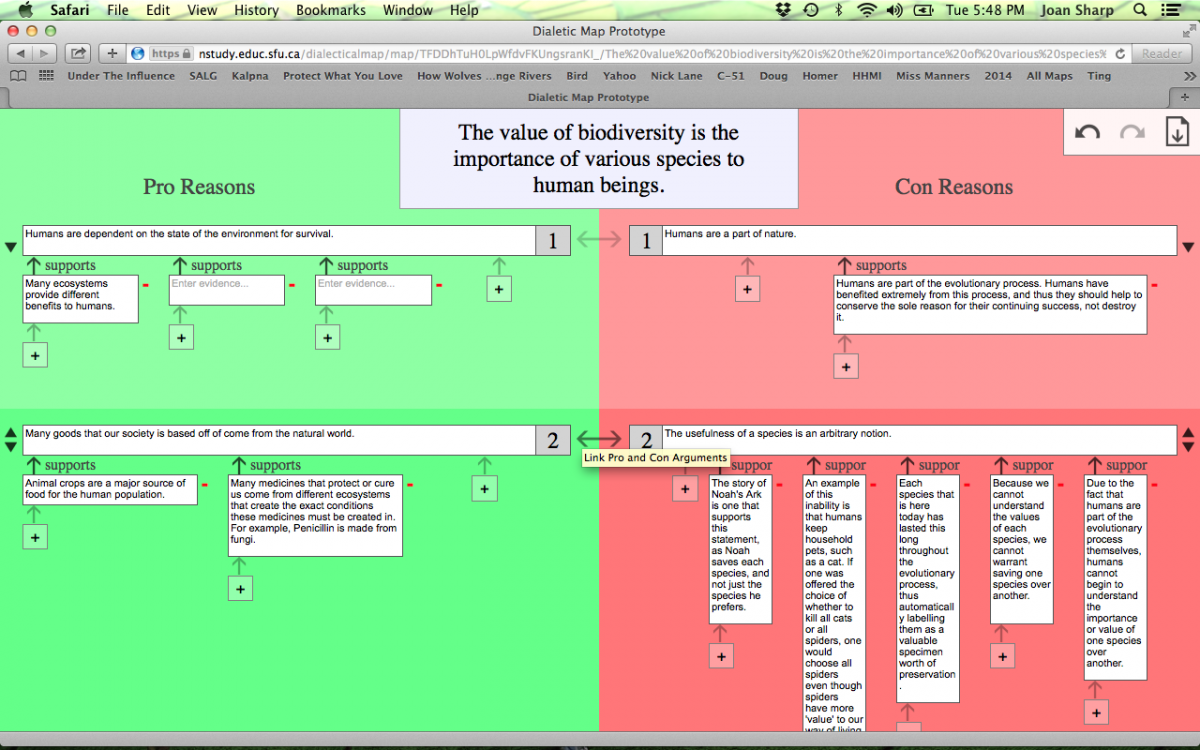

The dialectical map provides a web-based form that students complete. The instructor posts a statement or question, and the students have to give reasons both for and against the statement. Typical statement/questions are:

- ‘Wolves in northern British Columbia should be culled to protect biodiversity’ or

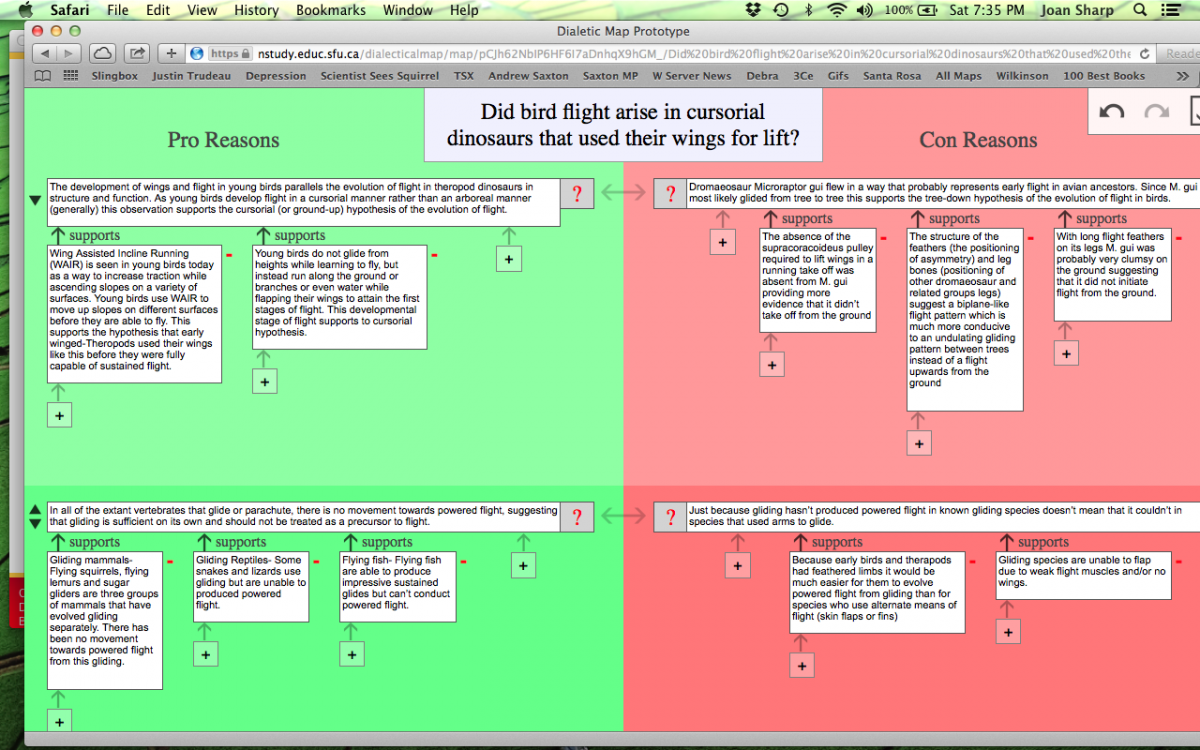

- ‘Did bird flight originate in cursorial dinosaurs that used their wings for lift?’

As well as boxes for reasons for and against (‘reason boxes’), there are also boxes where students post evidence in support of the reason (‘evidence boxes’), and a third type of box where students can elaborate on why the evidence supports the reason (‘warrant boxes’).

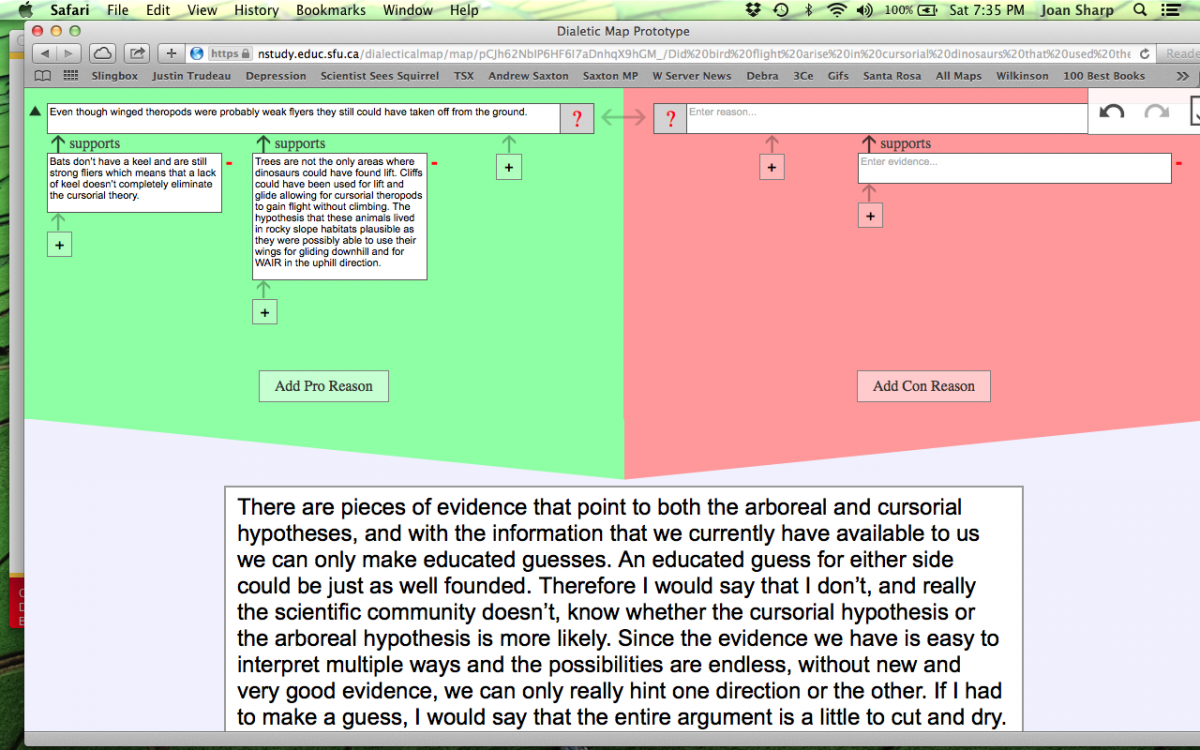

At the end of the map is a box where students are required to come to a conclusion.

A screen shot from a first year student’s dialectical map.

Students can rate the ‘strength’ of a reason from 1-5, and link reasons for and against that are related.

Once the student completes the form, ‘the ‘argument’ in terms of reasons, evidence and warrants can be printed out in text format by both the student and the instructor.

Professor Sharp uses the dialectical map in a variety of ways, depending on the level of the course and the nature of the topic.

In the first dialectical map, Professor Sharp provides students with a single inclusive reading and asks them to provide at least two reasons for and against the statement or alternate hypotheses provided in the DM. The goal of the first DM is to increase student familiarity with the tool. They are given full marks for conscientious completion of the map, but are also provided with feedback on the quality and relevance of their reasons and evidence (and warrants) and are told what mark they would earn if the quality of their map were to be graded.

In subsequent exercises using a dialectical map, the students are given scholarly papers to read before completing the map, but are also encouraged to research other sources that may strengthen the arguments, such as government reports or news articles.

When Professor Sharp poses a question (vs. a statement) in a dialectical map, students provide reasons supporting two alternate hypotheses that are clearly laid out in the assignment. This is how the tool is used in Vertebrate Biology, a third year course.

Usually students use three maps during a one semester course, receiving individual feedback from the instructor.

Class sizes are in the order of 50-90 students. Often there is a question in the final exam on one of the topics covered in a dialectical map.

Screen shots from a third year student’s dialectical map. It can be seen that the dialectical maps allow for a wide range of differences in complexity in developing arguments.

Benefits and outcomes

Professor Sharp saw a marked improvement in the quality of student arguments over a one semester term where the map is used three times, and this is reflected not just in the maps themselves but in the student responses to the final course exam questions.

Professor Nesbit and his graduate students in the Faculty of Education are conducting research into argumentation. Using information gathered by the dialectical map plus assessments of the quality of students’ essays, Professor Nesbit and his team are developing and progressively refining a comprehensive educational theory of argumentative writing.

Challenges and enhancements

It takes an instructor a little while to work out how best to use the online dialectical map, and in particular choosing the right level of question or topic that the students can handle.

Professor Sharp has found that three dialectical maps with individual feedback on each one is manageable with a class of 60 - 90 students without any assistance from teaching assistants. She believes it would be possible to train TAs to provide individual feedback on dialectical maps in order to use them in large introductory classes (300-500 students). If a general biology course was deemed a suitable place to introduce students to argumentation and to provide the opportunity for practice, it might be suitable to replace other written assignments with dialectical maps.

Potential

The online dialectical map has the potential for use in a wide range of subject disciplines. It has already been applied in educational psychology, science and engineering at SFU.

This is a research-based tool that is easy to use by both instructors and students for developing the essential 21st century skill of evidence-based argumentation.

Further information

Professor Joan Sharp

Department of Biological Sciences

Simon Fraser University

Burnaby, British Columbia

[email protected]

Professor John Nesbit

Faculty of Education

Simon Fraser University

Burnaby, British Columbia

[email protected]