In Ontario, it's expected that all post-secondary students will be digitally fluent. However, what does that even mean? Does it just refer to the ability to use basic digital tools like word processing software , search engines, and web browsers, or does it encompass a broader range of skills needed to succeed in a digital world? And how does it differ from digital literacy or digital competency?

Despite years of discussion and research, there is still no clear agreement on the exact meaning of these terms. As technology continues to advance, the definition of digital fluency continues to evolve.

Let’s reflect on the meaning of digital fluency and how it relates to digital literacy and competency. We will then conclude with a framework to guide assessment of the digital fluency of Ontario post-secondary students.

Evolution and diversity of the meaning of digital fluency

The term digital fluency evolved more recently out of the concept of digital literacy.

As technology evolved in the 1990s, educators began using terms such as computer literacy, information literacy, and media literacy recognizing that being literate requires not only fluency in language, but also being technologically proficient. In his seminal book, Digital Literacy, Paul Gilster coined the term digital literacy as “the ability to understand and use information in multiple formats from a wide range of sources when it is presented via computers” (Gilster 1997, p. 1). Gilster’s publication thus led to the widespread adoption of the term digital literacy.

From the early 2000s onward, the definition of digital literacy began a transformation from a purely informational and operational emphasis on technology utilization to an increased emphasis on knowledge-oriented cognitive, critical, and responsible perspectives (Spante et al., 2018).

For example, in the higher education context, and Sharpe and Beetham (2010) defined digital literacy as the “functional access, skills and practices necessary to become a confident, agile adopter of a range of technologies for personal, academic and professional use.” They developed a pyramid model depicting acquisition of digital skills from basic to complex that became influential at the time.

Shortly afterward, Eshet (2012) argued that digital literacy requires more than having the ability to operate a digital device; it requires mastery of a variety of complex cognitive, motor, sociological, and emotional skills. Similarly, Chan et al. (2017) saw it as “the ability to understand and use information in multiple formats with emphasis on critical thinking rather than information and communication technology skills.” This view of digital literacy as a multifaceted concept made up of a variety of cognitive, social, and attitudinal factors now prevails in the literature.

Despite the broader contemporary interpretation of digital literacy, some educators feel the term does not sufficiently convey the need for students to have more than just the knowledge and skills to use technology (Pelzel, 2019). They believe students must also be able create new knowledge with digital tools. To reflect this notion, they began using the term digital fluency. At the same time, others more concerned with employment skills began using the term digital competence. This term emphasizes knowing how to apply digital skills to complete a project.

If a broad view of digital literacy is taken, such as Chan et al.’s (2017), digital literacy subsumes the terms fluency and competency. On the other hand, if literacy is defined more narrowly as simply knowing how to operate digital tools, digital literacy would be seen as a prerequisite to fluency and competency.

Let’s use the term digital fluency to ensure a broad perspective is taken. At the same time, we recognize that one of the three terms – literacy, fluency, and competence – may resonate more strongly in some jurisdictions than in others.

Contemporary definitions of digital literacy, competency, and fluency

Contemporary definitions of digital literacy, competency, and fluency abound, and tend to reflect an organization’s mission. For example, UNESCO focuses on adult literacy and lifelong learning and provides the following definition:

Digital literacy is the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate, and create information safely and appropriately through digital technologies for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship. It includes competences that are variously referred to as computer literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy, and media literacy. (UNESCO, 2018)

EDUCAUSE, the higher education technology organization, defines the concept more broadly as encompassing:

A range of skills and knowledge necessary to evaluate, use, and create digital information in various forms. Digital literacies include data literacy, information literacy, visual literacy, media literacy, and meta-literacy, as well as related capacities for assessing social and ethical issues in our digital world. (EDUCAUSE, 2019)

The Council of the European Union emphasizes security and critical thinking, and uses the term digital competency to mean:

The confident, critical, and responsible use of, and engagement with, digital technologies for learning, at work, and for participation in society. It includes information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, media literacy, digital content creation (including programming), safety (including digital well-being and competences related to cybersecurity), intellectual property related questions, problem solving and critical thinking. (Council of the European Union, 2018)

Jisc, the UK digital technology not-for-profit agency focused on higher education research and innovation, uses the less common term digital capability to mean:

Digital capability is the term we use to describe the skills and attitudes that individuals and organisations need if they are to thrive in today's world. At an individual level we define digital capabilities as those which equip someone to live, learn and work in a digital society. (Jisc, 2022)

Digital fluency is not used as often as digital literacy and competency. For a campus-wide initiative, The Pennsylvania State University, defines digital fluency as:

The ability to leverage technology to create new knowledge, new challenges, and new problems and to complement these with critical thinking, complex problem solving, and social intelligence to solve the new challenges…[it consists of] an evolving collection of fluencies including, but not limited to, curiosity fluency, communication fluency, creation fluency, data fluency, and innovation fluency. (Sparrow, 2018)

Much work has been done at the K-12 level on defining digital literacy. Most prominent is the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), who began developing educational technology standards for students in 2007. Their leadership in this area prompted many provinces and U.S. states to base their digital literacy strategies on the ISTE’s digital learning framework. They state:

Digital literacy is the knowledge of and ability to use digital technologies to locate information; evaluate information; synthesize, create, and communicate information; and understand the human and technological complexities of a digital media landscape. (ISTE, 2022)

In Ontario, the Ministry of Education’s most recent definition of digital literacy is:

Digital literacy involves the ability to solve problems using technology in a safe, legal, and ethically responsible manner. With the ever-expanding role of digitalization and big data in the modern world, digital literacy also means having strong data literacy skills and the ability to engage with emerging technologies. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2020-23)

From this sampling of definitions, we draw the following conclusions:

- Definitions of digital fluency, digital literacy, and digital competency often overlap.

- Digital fluency is a more complex concept than technology proficiency and encompasses a variety of factors including social, ethical, critical thinking, and creativity.

- Achievement of digital fluency is not an aim in and of itself but is intended to prepare learners to participate fully in our digital society.

- Most importantly, none of the definitions directly or arguably indirectly address the ability to learn online, except for Jisc’s. The COVID-19 pandemic, with the overnight shift to online learning around the world, illustrated that being able to learn online is an essential skill and will continue to remain so and must be included in any definition of digital fluency.

Given the above review of definitions and these conclusions, we define digital fluency as:

The knowledge and skills to use technology responsibly and securely to find information and evaluate its reliability, communicate, create, learn and work online, and understand how technology affects our lives.

Assessment of digital fluency

As there are no digital fluency frameworks used by major organizations for assessment, we highlight two digital literacy frameworks that take a broad view of literacy that overlap with digital fluency. The frameworks build on the organization’s definition of digital literacy and provide key factors of the definition that can be assessed.

Jisc’s framework

The first is Jisc’s framework which builds on the definition cited above. It consists of six digital capabilities:

- Digital proficiency and productivity (functional skills)

- Information, data, and media literacies (critical use)

- Digital creation, problem solving and innovation (creative production)

- Digital communication, collaboration, and participation (participation)

- Digital learning and development (development)

- Digital identity and wellbeing (self-actualising)

Detailed role profiles were developed that follows a student’s journey from entry into a higher education program, when they are at the end of first year, and upon graduation. The profiles can serve as guides for program planning and review, resource preparation, and a basis for assessment.

For example, for the criterion Digital Identity, students at the entry level would be expected to “Consider digital identity and reputation when communicating online; at the end of year one “Understand how personal data is collected and used by different platforms, read terms and conditions and restrict data sharing as preferred;” and by the end of their studies “Regularly manage at least one personal site (e.g., blog, professional profile, channel, website).”

The role profiles are specific enough to be able to create survey questions to assess student literacy. Prior to that, a decision would have to be made about the student level to assess (i.e., entry, first year, or program completion) and the criteria would have to be reviewed for relevancy to the Ontario context.

ISTE-Dell framework

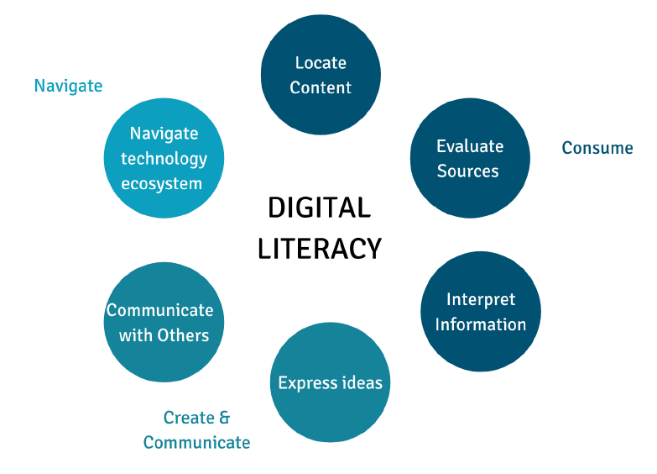

ISTE recently partnered with Dell Technologies on a project called Get Digital Skills with the goal of improving digital literacy in schools and the general population. Starting with ISTE’s definition of digital literacy (cited above), they developed a framework based on work already done by ISTE in this area as well as that of several other well-regarded organizations. The framework sets out three overarching digital literacy skill areas:

- Navigation

- Consumption and creation

- Communication

Within these areas there are six specific subskills they believe everyone should possess. A visualization of the framework is below.

- Locate content

- Evaluate sources

- Interpret information

- Express ideas

- Communicate with others

- Navigate technology ecosystems

For each of the six areas the project developed online self-assessment questions. Questionnaires are available for learners, educators, and caregivers (parents/guardians). The learner questionnaire tends to be focused on K-12 students, however some questions would be appropriate for post-secondary students.

For example, a question on locating content is:

Advanced searching can help you get the best results. How familiar are you with advanced search strategies like "exact words or phrase" searches, locating results within a specific date range, or searching by file type?

- Very familiar - I know a lot

- Somewhat familiar - I know a few tricks

- Not too familiar - I would like to know more

- Unfamiliar - I have a lot to learn

A valuable feature of this project is that upon completion of the questionnaire, links to digital resources for self-study are recommended depending on the answers given. This provides an extrinsic reward for those who complete the questionnaire by providing helpful information, rather than simply the intrinsic reward of doing something someone asks of them.

Moving forward with assessment

We are creating a model which will guide development of a survey for Ontario post-secondary students on their digital fluency skills.

The model draws upon aspects of the Jisc and ISTE-Dell frameworks, although neither appear suitable to be adopted in their entirety because they do not focus specifically on digital fluency. Moreover, the Jisc framework is focused on skills within a specific academic discipline, whereas the ISTE-Dell framework is aimed more at K-12 students and educators.

The model guides the assessment of digital fluency in seven key domains:

- Locating Content

- Evaluating content

- Communicating

- Creating

- Learning online

- Working online

- Recognizing societal impact

Digital fluency is an essential set of skills all Ontario post-secondary students must possess to succeed in our society, and our next step is to develop and field test survey questions to assess their proficiency levels.

References

Chan, B. S., Churchill, D., & Chiu, T. K. (2017). Digital literacy learning in higher education through digital storytelling approach. Journal of International Education Research, 13(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.19030/jier.v13i1.9907

Eshet, Y. (2012). Thinking in the digital era: A revised model for digital literacy. Issues in informing science and information technology, 9(2), 267-276. https://doi.org/10.28945/1621

Gilster, P. (1997). Digital literacy. New York: Wiley.

Sharpe, R., & Beetham, H. (2010). Understanding students’ uses of technology for learning: Towards creative appropriation. In R. Sharpe, H. Beetham, & S. De Freitas (Eds.), Rethinking learning for the digital age: How learners shape their experiences (pp. 85–99). London: Routledge.

Spante, M., Hashemi, S. S., Lundin, M., & Algers, A. (2018). Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1519143. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1519143